What is philosophy? Where is it found, and who practices it?

We might try to answer these questions the way we would for any other science — i.e., any other organized body of knowledge and intellectual inquiry — by considering its subject matter. Normally this is pretty easy: botany studies plants, geology is knowledge about rocks, medicine is about the means of moving people from disease into health. But in the case of philosophy, the very subject matter has been hotly contested, and has shifted widely over the centuries.

We might instead try to identify a historical lineage for the subject. We could locate the first people to use the term “philosophy” (or rather, its Greek antecedent philosophia) as the name for what they do, and then trace the path by which that name or title has been handed down through the generations. But would such a series of historical accidents really tell us anything about what philosophy is?

And what about other peoples, other cultures and civilizations? If “philosophy” is only a matter of historical descent, then indigenous traditions — whether of the literate urban civilizations of India, China, and Mesoamerica, or in the oral traditions of countless other societies around the globe — would be excluded from the outset from counting as philosophy, even if the questions they raise, the methods they employ, and the answers they discover, resemble very closely those of the direct inheritors of the Greek project.

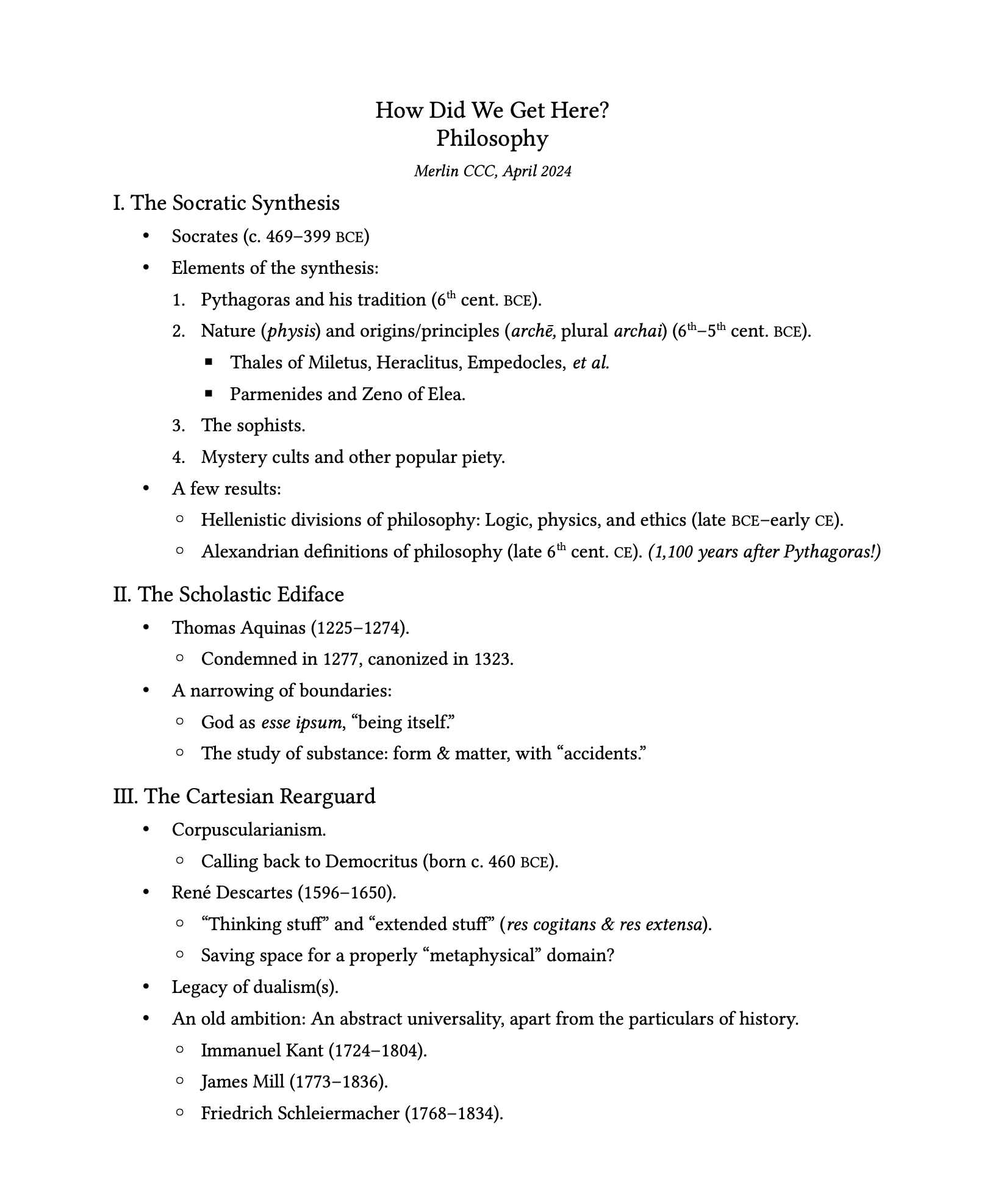

In this evening’s program, we looked at some of the major ways in which the concept of philosophy has evolved over the centuries: through the successes and failures internal to the work of self-described philosophers, as well as through dialogue with developments in the other human and natural sciences, responses to the often-hegemonic demands of religious and political authorities, and the encounters of Western intellectuals with the robust intellectual and scientific traditions of other civilizations.

In doing so, we traced some of the important ways in which philosophers have understood the subject-matter of their discipline. And we examined how, from very early on, philosophers have been especially self-conscious of the history of philosophy, in a way that is unique from other sciences: the history of botany, for example, is a different subject from the actual study of plants, whereas from very early days, telling the history of the philosophy is seen as an important part of the practice of philosophy itself. Why should that be the case, and what does it teach us about what philosophy is?

Photos

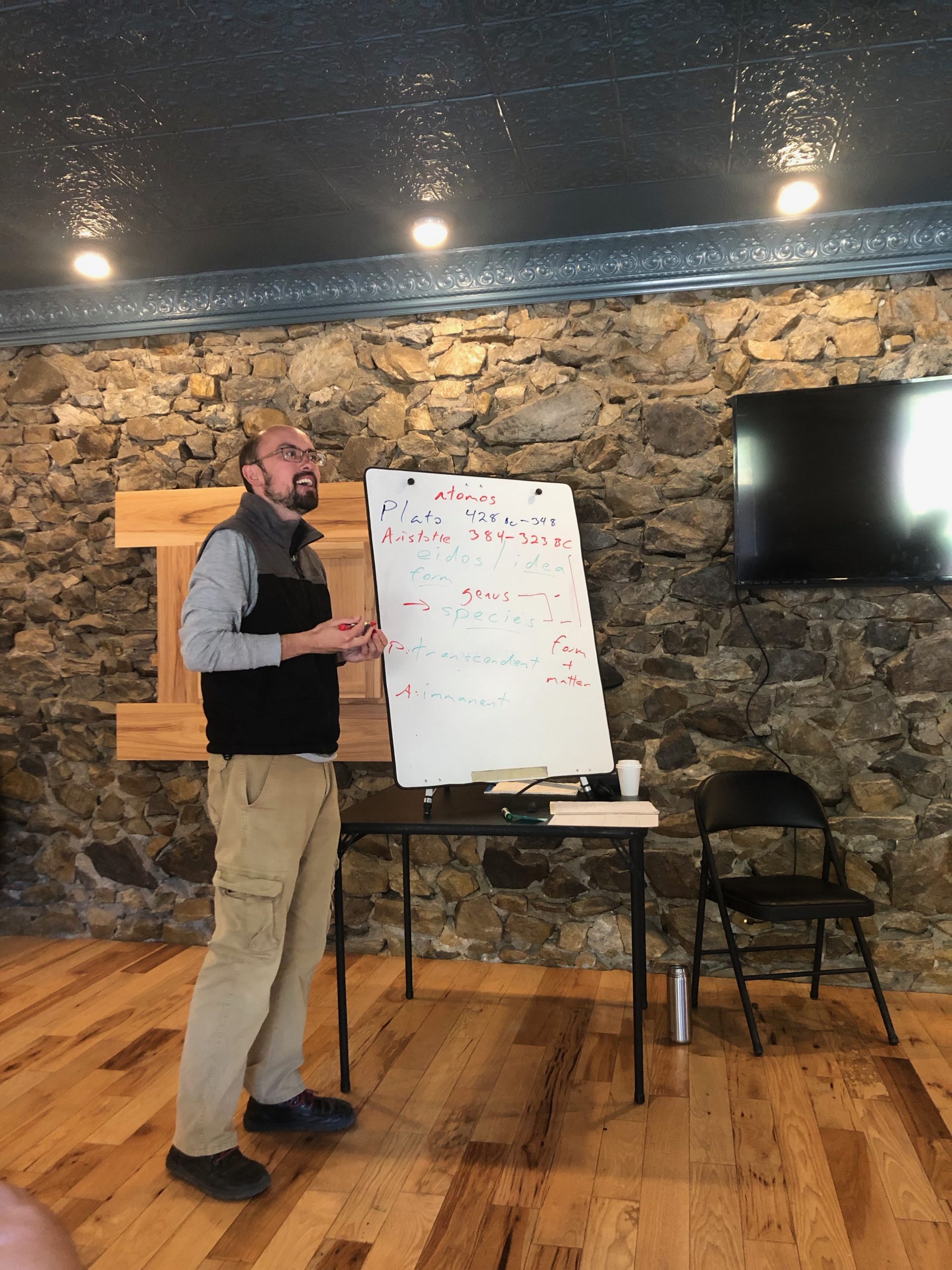

About David

David Nowakowski is as a philosopher and educator in the Helena area whose professional work is dedicated to helping people of all ages and backgrounds access, understand, and apply the traditions of ancient philosophy to their own lives. David began studying ancient philosophies and classical languages in 2001, and has continued ever since. A scholar of the philosophical traditions of the ancient Mediterranean (Greece, Rome, and North Africa) and of the Indian subcontinent, reading Sanskrit, Latin, and classical Greek, he earned his Ph.D. in philosophy from Princeton University in 2014. His work has appeared in a variety of scholarly journals, including Philosophy East & West, Asian Philosophy, and the Journal of Indian Philosophy, as well as in presentations to academic audiences at Harvard, Columbia University, the University of Toronto, Yale-NUS College in Singapore, and elsewhere.

After half a decade teaching at liberal arts colleges in the northeast, David chose to leave the academy in order to focus his energies on the transformative value of these ancient philosophical and spiritual traditions in his own life and practice, and on building new systems of education and community learning that will make this rich heritage alive and available to others.