What is (a) religion? What are religions for? Whom are they for? And conversely, if someone is “spiritual but not religious” (or simply not religious), what exactly is it that they aren’t?

In this evening’s program, we explored some of the ways that the concept of “religion” has evolved and radically changed over time, along with the related concepts of spirituality and atheism. We also looked at some of the social, political, and historical factors which have spurred changes in dominant and popular notions of religion, without necessarily reducing the domain of religion to merely those other factors.

In the course of our survey, we met a wide range of thinkers spanning more than two millennia, and spread across five continents (with apologies to Australia), including:

- Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BCE)

- Jewish philosopher and theologian Philo of Alexandria (13 BCE–50 CE)

- Early Christian “father of the church” Tertullian (155–220 CE)

- Syrian philosopher and priest Iamblichus of Chalcis (245–325 CE)

- Florentine translator and magician Marcilio Ficino (1433–1499)

- English political theorists Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and John Locke (1632–1704)

- Romantic poets John Keats (1795–1821) and Percy Shelley (1792–1822)

- American psychologist William James (1842–1910)

- German philosopher and theologian Rudolf Otto (1869–1937)

- Swiss psychologist Carl Jung (1875–1961)

- Yanomami philosopher and shaman Davi Kopenawa (1956—present)

- And others…

Some of these thinkers are highly innovative and original, setting a course for future generations, while others give especially clear expression to dominant or widely-held views of particular places, times, and cultures.

As we considered the contributions of these and other individuals and communities, we found ourselves returning to a variety of conceptual and theoretic issues, on which our various thinkers took radically different positions:

- Is religion more of a private matter, which mostly belongs to individuals, families, or freely-chosen affinity groups, or it is primarily more public, belonging to ethnic groups, tribes, states, or whole civilizations?

- Are religions most properly local or particular, such that we’d naturally expect a wide diversity of religions across the wide diversity of humanity, or are they (or should they be) universal in their scope, applicability, and/or authority?

- What are the most natural responses, to noticing that your neighbors, or various foreigners, have different Gods, different religious beliefs and practices from your own?

- Where are the boundaries between religion and spirituality, or between religion and superstition? And where is atheism, amidst this tangle of concepts?

- What is the relationship between religions and human cultures?

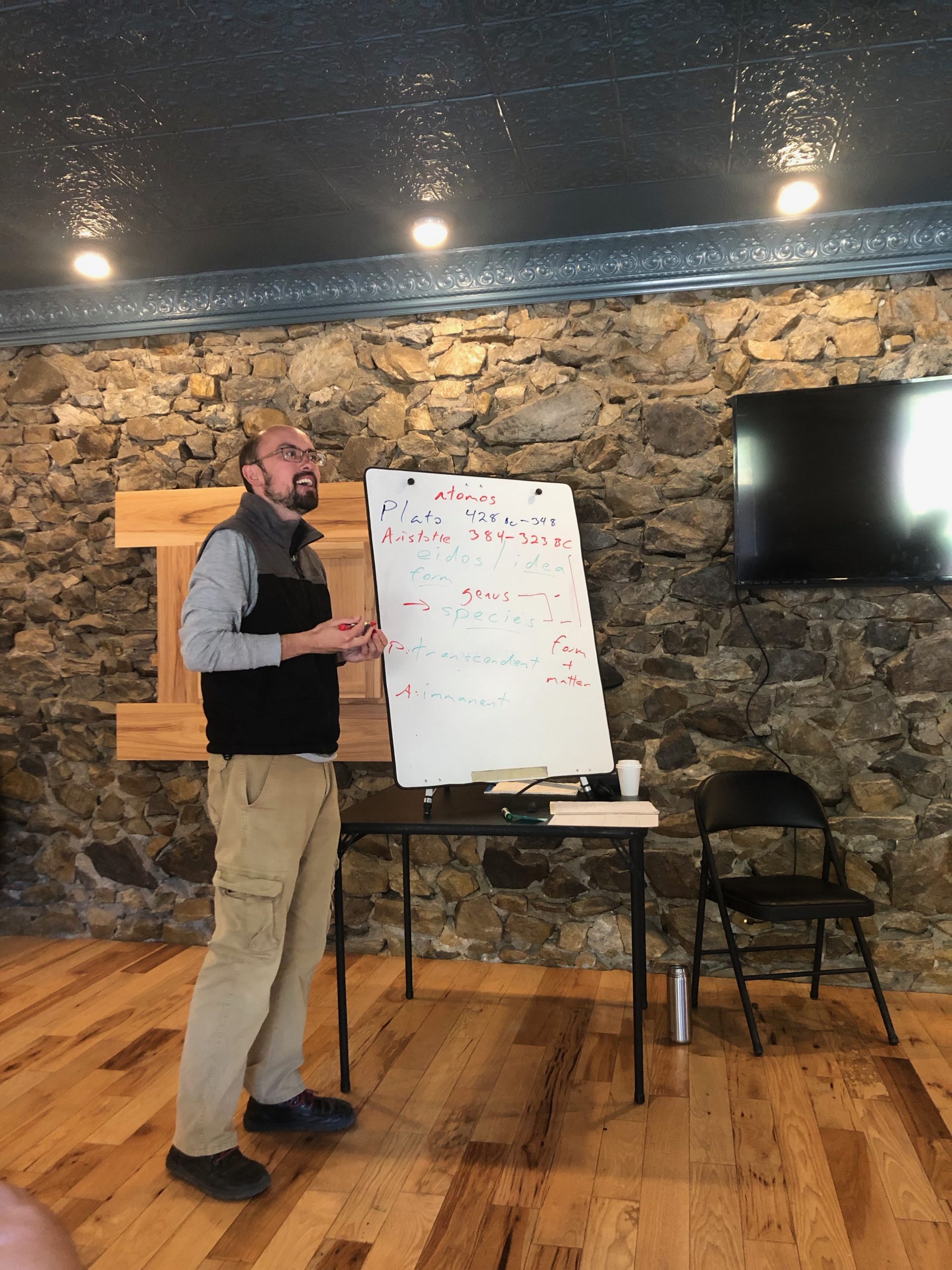

Photos

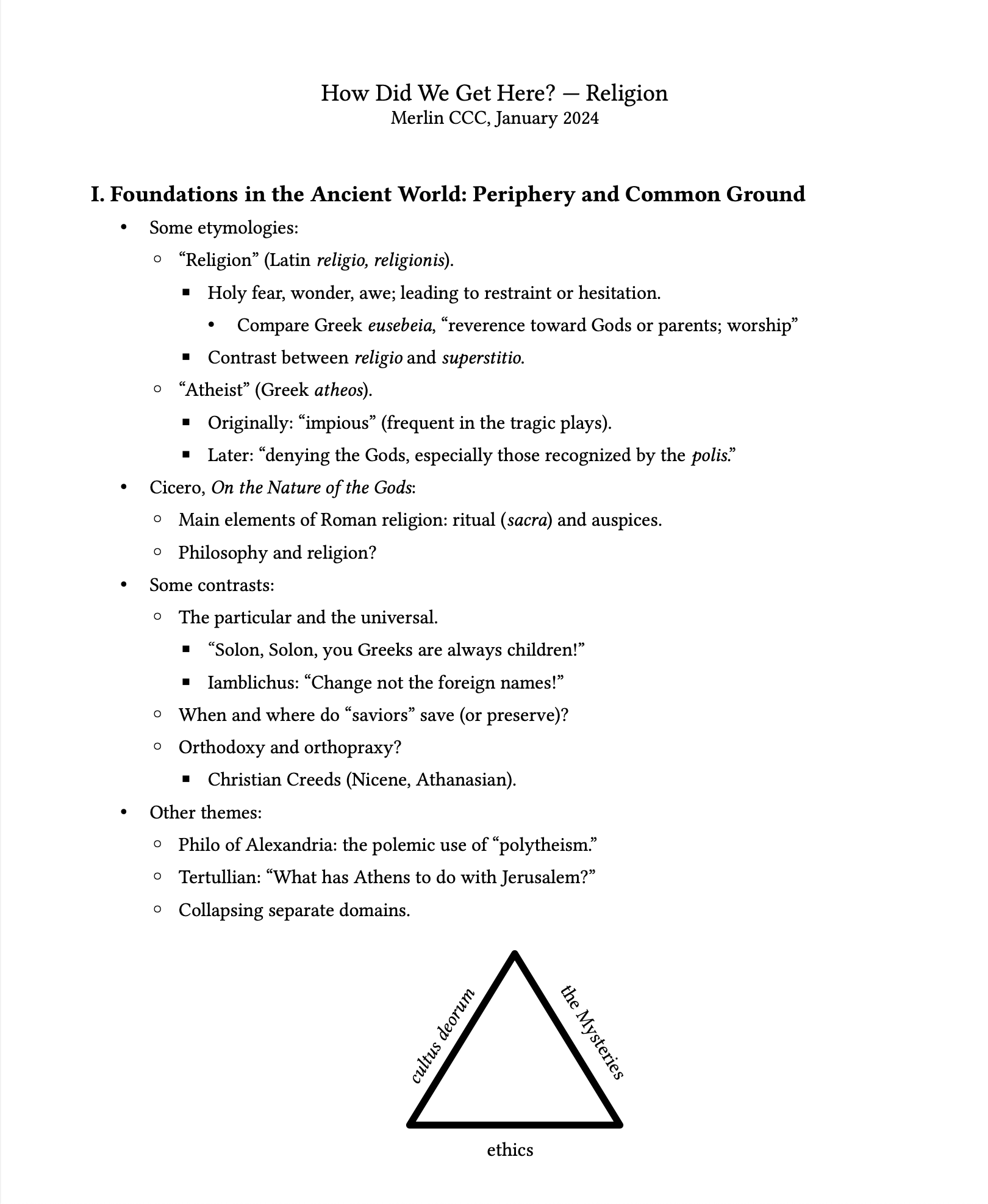

Click on the image below to view/download the pdf.

About David

David Nowakowski is as a philosopher and educator in the Helena area whose professional work is dedicated to helping people of all ages and backgrounds access, understand, and apply the traditions of ancient philosophy to their own lives. David began studying ancient philosophies and classical languages in 2001, and has continued ever since. A scholar of the philosophical traditions of the ancient Mediterranean (Greece, Rome, and North Africa) and of the Indian subcontinent, reading Sanskrit, Latin, and classical Greek, he earned his Ph.D. in philosophy from Princeton University in 2014. His work has appeared in a variety of scholarly journals, including Philosophy East & West, Asian Philosophy, and the Journal of Indian Philosophy, as well as in presentations to academic audiences at Harvard, Columbia University, the University of Toronto, Yale-NUS College in Singapore, and elsewhere.

After half a decade teaching at liberal arts colleges in the northeast, David chose to leave the academy in order to focus his energies on the transformative value of these ancient philosophical and spiritual traditions in his own life and practice, and on building new systems of education and community learning that will make this rich heritage alive and available to others.