We often take “labor” and “work” as synonyms, describing an often-difficult process that’s required to “get by” in life, or even to “make our living.” Yet there’s also a strong contrast between the demanding-yet-fulfilling “work” of an artist, and the drudgery of someone laboring in a factory.

Then there are other complicated dances — both in theory, and in the day-to-day organizing of our lives — between labor and leisure, work and recreation, action and contemplation, “liberal” and “servile” pursuits. These complications have been viewed very differently across the centuries.

Among other things, the complex history of “labor” and “work” invites us to ask:

- How do the toil of labor and the accomplishments of work relate to one another, and to other parts of human life?

- What roles do work and labor play, in the pursuit of a good, fulfilling, complete individual life?

- What roles do they play in forming our human communities, and shaping our public, collective, and social life together with one another?

- Is labor something to be embraced, as the most fundamental source of value, or is it something that we have to escape from, in order to reach our full human potential?

- How do work and labor situate humans within — or help us to escape from — larger patterns of time and eternity, of life and death?

In this “How Did We Get Here?” event, we set out a variety of different answers to these questions, as seen by different communities whose complex legacy we’ve inherited.

We began with classic literary sources, ranging from the Greek poet Hesiod’s agricultural tips in the Works and Days, to the practical advice given in the voice of Odin in the Old Norse Hávamál. Here, we reflected on the ways that for traditional European societies, the necessity of labor both allows for, and is in tension with, the public life shared by free citizens, and the possibilities those citizens have for extending their memory and influence beyond their individual deaths. And in doing so, we saw a sharp contrast between work that endures, and the toil and drudgery of mere labor.

We then considered some intellectual, historical, and religious factors that led to changes in these understandings, notably the “cosmopolitan” ethics of early Stoicism, the rise of the Roman Empire, and the ideal of “renouncing the world” in early Christianity. In each of these movements, we reflected on the dynamic interplay between abstract theory and “conditions on the ground”, and contrasted the different sorts of respect (or contempt!) which are given to labor, leisure, and public life within each of them.

Drawing closer to the present, we looked at some ways in which historical and economic factors have become reflected in philosophical concepts, or justified after the fact: the Christian church’s shift from renouncing the world to ruling it; the rise of craft and merchant guilds in the European Middle Ages; and the Industrial Revolution and its critics. In each case, we asked: from this vantage point, what seems most “natural” about the relations between work, labor, human freedom, and the common good?

And as we got closer to the present, we checked in with social and political theorists ranging from John Locke and Adam Smith, to Karl Marx and Hannah Arendt, to take stock of some ways in which each of these transformations upended older ways of thinking about labor, work, and humanity.

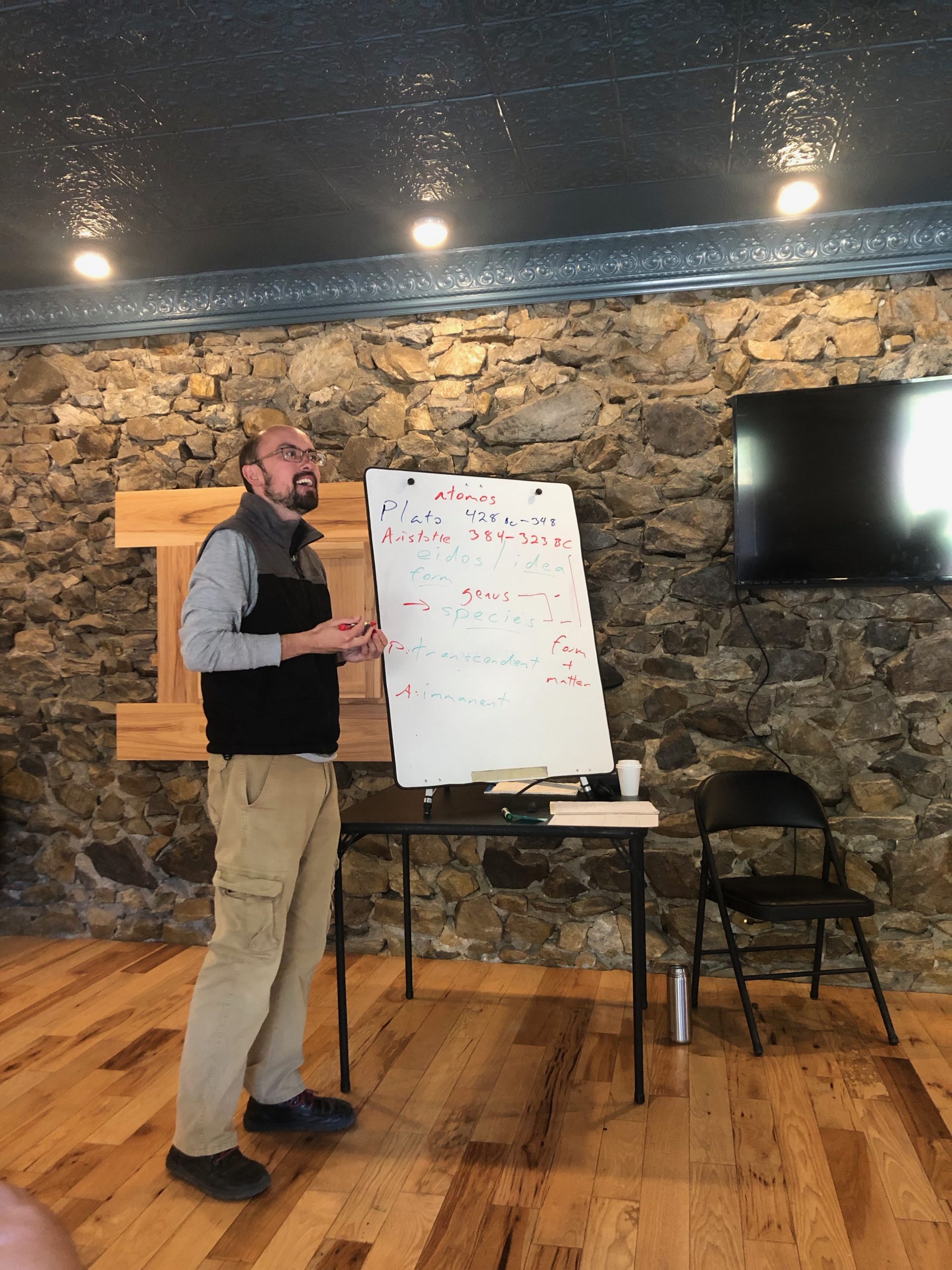

Photos

About David

David Nowakowski is as a philosopher and educator in the Helena area whose professional work is dedicated to helping people of all ages and backgrounds access, understand, and apply the traditions of ancient philosophy to their own lives. David began studying ancient philosophies and classical languages in 2001, and has continued ever since. A scholar of the philosophical traditions of the ancient Mediterranean (Greece, Rome, and North Africa) and of the Indian subcontinent, reading Sanskrit, Latin, and classical Greek, he earned his Ph.D. in philosophy from Princeton University in 2014. His work has appeared in a variety of scholarly journals, including Philosophy East & West, Asian Philosophy, and the Journal of Indian Philosophy, as well as in presentations to academic audiences at Harvard, Columbia University, the University of Toronto, Yale-NUS College in Singapore, and elsewhere.

After half a decade teaching at liberal arts colleges in the northeast, David chose to leave the academy in order to focus his energies on the transformative value of these ancient philosophical and spiritual traditions in his own life and practice, and on building new systems of education and community learning that will make this rich heritage alive and available to others.

Thank You’s

Thank you to David Nowakowski and the Helena community for helping to make this event a success! Thank you also to the American Philosophy Association and the Berry Fund for Public Philosophy for grant funds helping to support activities like these in our community…as well as our sustaining donors!!